To start: I am not claiming to be a mouthpiece for the Faroese. The Islands are made up of individuals, most of whom hold degrees and are starkly different from one another. Certainly not everyone shares the same views; I met many Faroese who were vehemently against whaling. One thing is also for sure: we are not discussing a community of ‘barbarians,’ but instead those of a proud and weathered culture that extends back hundreds upon hundreds of years.

I’ll also begin by saying that I will remain neutral in my essay on the Grindadráp (the Faroese name for the slaughter of inland pilot whales, most often abbreviated as just ‘Grind’). I have tried whale meat because it is a local culture’s delicacy and I was offered it — I’ll talk about that experience below. When I remove my emotional reaction to the Grind, and look at it objectively, I find that both activists (namely Sea Shepherd, the main outspoken voice against the tradition) and the Faroese have equally valid arguments. And they can’t hear each others over the shitstorm constantly brewing on social media.

This is an attempt to explain the Faroese point of view.

Hopefully, I can present an honest and unbiased discourse. This post is only part 1 of 2 — the other half of the discussion can be found here: Faroese Whaling, in the Eyes of Activists.

First, my experience with the Grind… I stayed in Miðvágur on my very first night in the Faroe Islands. I woke up to the town’s idyllic river tinted red. As if it were a welcoming party, a squad of 132 whales were killed early that gray morning.

With dew in my eyes, I walked down to the docks and stood among villagers. I watched Faroese fishermen hoist countless whale carcasses out of the bloody water with forklifts. They were lined up and their bellies were split to spill their guts. Many of them seemed to have terror frozen on their faces.

There was a solemn air to the event — different from the Vice documentary that captured children jumping off of hacked blubber and picking up unborn whale fetuses. Everyone working did so without chit-chat, swiftly. Onlookers gazed with silent curiosity. The scene, the Grind itself, was absolutely brutal, and I don’t think any Faroese person would deny that.

My second Grind experience was when I rode along with a Faroese friend who was delivering a portioned hunk of whale meat to a relative in Torshavn. I asked to try lifting it — though a slab only about a foot in length, it had to be carried in a tough garbage bag. That stuff is dense and heavy.

This delivery was part of the islands’ distribution of meat to every member of the community, for cooking. It was my first bit of evidence that the haul from the slaughter actually was indeed being used for its intended purpose (and divided in the way the Faroese claim): from fishermen to families to extended families and friends. Everyone interested gets a cut, and there is no money involved.

My last experience with the Grind was at a homey Faroese dinner with friends. We were all chatting jovially, drinking Föroya Bjór, and admiring the different traditional fare: dried fish, thinly-sliced mutton, grated pickled beets, and rundstykkir, among other delicious dishes. Then, in a grand entrance, a friend balanced a large silver platter loaded up with dark black Grind meat, thin bits of blubber, and cold boiled potatoes.

The meat, of which I took only a fingernail’s bite, was softer than anticipated, and tasted unlike any other meat I’ve tried. It wasn’t particularly pleasant — very very dark, and it filled my nostrils with the same smell from the slaughter a few days earlier. I imagine it’s an acquired taste. The blubber was like lard. It wasn’t chewy, but instead it almost melted in the mouth. Meaty butter. The potatoes were potatoes.

There was a definite air of taboo surrounding the meal. With foreigners (and whale meat) present, the politics of the Grindadráp eventually boiled to the top of the dinner conversation. The Faroese were fiery in the their defense of the Grind — it was obvious that they felt their position (and tradition) were under undue criticism.

(**To any readers who feel that a point is missing or misrepresented, please join the discussion with a comment at the bottom of this page. I’ll try to keep this post current and accurate. My personal thoughts are indented.)

The first point that one will bring up in the defense of the Grind is that everything that is killed gets eaten. While this is not really true (the tail fins and skeleton of the whales simply get thrown back into the sea), all of the edible portions are used. It is distributed equally and for free among the community.

The greater question is: Is the whale meat necessary food? The Faroese have access to supermarkets and modern imports like the rest of Scandinavia. Activists ask: ‘Why do they need to eat Grind meat if it not essential (or even harmful) to their health?’

The paraphrased Faroese answer is blunt: ‘Because we like it.’ Then follows an explanation: ‘Why should most every other culture that eats meat face less-scrutiny? Why are we so criticized? We go out and kill the whales with our own hands — it is not bought pre-wrapped and packaged. We have a connection to the animals. We love the taste of whale; it is a delicacy to us. Don’t your cultures have delicacies? The Faroese do not send activists to your factories or coastlines. Why should our tradition be squashed simply because of the kind of meat?’

The Faroese are proud to announce that they keep logs dating back decades. These books of information carefully track not only past migratory movements, but also the numbers and vitality of pilot whale pods. The fishermen state that official numbers show sustainability among the pilot whale population — which is backed up by other estimates that pilot whales are not even threatened, much less endangered.

Claims that pilot whales are dying out, and that Grind is to blame, seem to be, simply put, statistically false. Those on the Faroes are also eager to express their willingness to stop whaling if the whale numbers started dwindling. They point to the puffins, which they stopped hunting for that very reason, as a past example.

All of the men who rush out into the water, with wild hooks and ropes flailing, must first pass a class on “proper whaling.” An individual is not allowed to participate in the Grind until they know how to kill “quickly and painlessly,” with a quick cut to the spine behind the head. Many of the more gruesome tools of the past “have been retired.” Those who have not shown credentials, or more particularly any disrupters, have been either arrested or barred from the beach in recent years.

That said, it is evident in videos of the Grind that the kill is not in fact painless for the whales; many flail and desperately try to escape before receiving their final blows. The faces of the whale corpses, when dragged ashore, are riddled with deep gashes. Do these moments of pain justify ending the ritual? Most Faroese argue that, compared to other kinds of hunting (‘a shot deer is in pain for hours before it dies’), hardly so. And most foreigners say ‘of course!,’ gagging at the brutality.

Several Faroese recounted an old saying singing the nutritional virtues of whale meat. Perhaps back in the day, when other protein was sparse and imports were seldom, this was true. But today, whale meat is advised against entirely by the Faroese Chief Medical Officer, and there are much healthier options on the Islands in markets. The whales are wrought with mercury from the pollution of other countries.

‘The rhetoric and the availability of bloody photos makes the Faroe Islands a perfect target for organizations like Sea Shepherd [the tourism office’s main antagonist]. The emotional reaction drawn by a photo of a cut-up whale is intense. People are willing to ignore facts or logic if they’re given a chance to criticize. Those driven to a pious cause will even donate to the organization that they believe is stopping the brutality…’

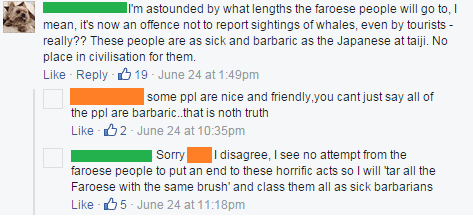

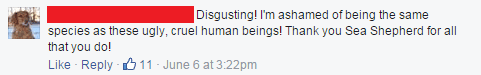

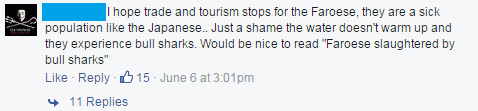

Many Faroese feel that organizations like Sea Shepherd paint the entirety of the Faroe Islands in an unfair light in order to garner widespread support and money from their fans. If one looks at the outlets of Sea Shepherd and notes their strong rhetoric, which slams not only the Grind but the entirety of the Faroe Islands, it’s easy to agree: “barbarians,” “ferocious,” “primitive” — all of these terms and worse have been used to describe all Faroese. And the number of voices lent to the activist organizations far outnumbers the population on the Faroe Islands.

There is another more uncomfortable point to this argument: the Faroese are European, first-world, and are held to a different standard than a country of a similar or even larger number. ‘The impact of seeing white men in knitted sweaters wade into the waters is perhaps more significant than the tribesmen of another land.’

Similar to point #6, many young Faroese are passionate about the Grind because they feel their culture is under siege. With a ‘f$#% the haters’ kind of attitude, they satirically support the whaling and vehemently (and vocally) hate those who they feel have smeared their entire country. When they speak out online, either logically or emotionally, they are met with a torrent of backlash that absolutely fuels the fire.

These same young people are taking office in the Faroe Islands and in Denmark. In recent times, laws have been established that protect whalers and prosecute disrupters. Is it any surprise that those who have grown up seeing things like:

have a hand in these changes?

This post is only 50% of the argument. Please see the other half here: Whaling, In the Eyes of the Activists.